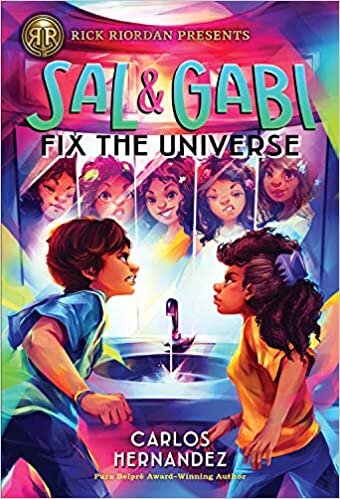

TITLE: Sal & Gabi Fix the Universe (Sal & Gabi #2)

AUTHOR: Carlos Hernandez

423 pages, Disney Hyperion, ISBN 9781368022835 (hardcover)

DESCRIPTION: (from the inside front cover): Will Sal’s Papi destroy the universe? Papi, a calamity physicist, believes he has made a breakthrough that will let him close all of the wormholes Sal and Gabi have made in the membrane between universes. But how will that affect Gabi’s baby brother, Iggy, who needs to be connected to another universe in order to remain healthy? And what will it mean for Sal, who uses the holes to stay in touch with other versions of his Mami Muerta? As if he needed more problems, a Gabi from a far-off world shows up determined to stop Sal’s papi at any cost. She believes that sealing all the holes will only bring about utter destruction. It’s already happening in her universe… While Sal works to keep both Papi and this other Gabi under control, he has to worry about finding a new home for Yasmany, and he’s also tasked with co-directing Culeco Academy’s performance of Alice in Wonderland for parent-teacher night. It’s a lot for one guy to juggle, even if he is a showman. Good thing he has some help – a multiverse full of friends and a few clever AIs. Wait … did that toilet just talk?

MY RATING: Five stars out of five.

MY THOUGHTS: Last year, I ended my review of Carlos Hernandez’s Sal & Gabi Break the Universe thusly: “Also: the sequel has been announced, and I cannot wait to find out how Sal & Gabi Fix the Universe and what happens before they do!”

Reader, I was not let down at all. Sal & Gabi Fix the Universe is full of all the humor, warmth, and creativity of its predecessor. It avoids the series sophomore slump neatly, telling a complete story of its own while still building on and enhancing the story of the first book. (I have no doubt a reader could pick this book up without having read the previous and not feel lost at all, so adept is Hernandez at working in the backstory while moving the current plot forward. But I definitely recommend reading them in order for greater character and world-building depth.) It increases the stakes the characters face naturally and in proportion to what has gone before (rather than cranking it up beyond 11 with little/no sense of logical escalation). And the characters are not static: they continue to grow and reveal themselves to the reader at surprising moments.

Fix the Universe continues to subvert the YA/MG trope that all the kids are good and smart and all the adults are evil or clueless, and that neither ever listens to the other. Sal, Gabi, Yasmany, and Aventura are smart—there’s no doubt about that – but they’re also plagued by insecurities that make them question the path forward. Unlike many other main characters, these kids are willing to talk about their issues with the adults in their lives. Not always without prodding, and not always completely – but eventually the necessary conversations do happen. The Vidón and Reál parents, Principal Torres, and the other teachers and school staff we see may occasionally be clueless – Coach Lynott particularly so – but they’re not completely uncaring or disconnected from what the kids under their care are going through. They do their best to listen to the kids and offer help finding solutions to whatever problems the kids present to them. Of course, Sal, Gabi and company don’t tell the adults about the biggest of the problems – the fact that “EvilGabi” wants to destroy the membrane between universes – until it’s almost too late. But the problems they are presented with? Finding a better living situation for Yasmany, helping redesign the big Parent-Teacher Night performance? The adults don’t solve these problems for the kids, they solve them with the kids, and pretty much let the kids take the lead. And when the kids break rules, there are firm and logical consequences: when events conspire so that Principal Torres thinks Sal, Gabi, and Yasmany have taken a “magic” trick too far, upsetting the whole school, the consequence is that Sal is not allowed to bring any of his tricks to school until he earns Principal Torres’ trust back.

In fact, Principal Torres shines in this book. The Vidón and Reál parents are all still an important part of the narrative, but Principal Torres is there at every turn, modeling what a good and effective school administrator should be like: concerned for her students’ health and welfare more than anything else. She makes clear her belief that hungry students are poor students, and that upset students are poor students. She feeds, she listens … but she’s also strict. Most of the teachers and staff follow her lead, some more than others, feeding students’ curiosity and creativity. Of course, not every adult is the ideal – but interestingly, Hernandez keeps the worst of these (Yasmany’s family) off-screen. We hear about how they treat him in a way that makes the harm they’re causing very clear and real, but we, and our narrator Sal, never have to actually see it.

While the adults fill certain roles, it’s the kids who are the focus, of course. One of the things I love about these books is how normal the kids are. No Perfect Heroes saving the day here. Sal, Gabi, and company are heroic precisely because they are not perfect but refuse to let their imperfections stand in their way. Sal knows his insecurities can hamper his friendships; Gabi knows she can be a bit too intense and overwhelming; Yasmany knows he needs to learn how to control his anger (toward others and toward himself) better; Aventura knows her single-mindedness sometimes causes her to lose sight of the bigger picture. The many ways these character traits collide throughout the book provide most of the narrative tension, much like in the first book. Hernandez could have eschewed all the sci-fi shenanigans and written a book about middle school kids navigating friendships and familial issues and it would have been just as excellent, because he understands how kids talk to each other and how their inner monologues burst into external conversation at the unlikeliest, and occasionally most inconvenient, times. The scenes of the kids working out their communications issues, acknowledging when they’ve wronged each other, then building each other up, are some of the best scenes in the book.

And a number of those scenes have to do with the nature of grief and how we deal with it. The grief manifests in several forms: Sal’s long-standing ache over the death of his mother matched with Senor Milagros, the head custodian’s, loss of a spouse and EvilGabi’s loss of a boyfriend, but also Yasmany’s grief over not having a family that loves him. Even the Reál family’s worries that baby Iggy will get sick again are a form of grief (anticipatory as it may be). Throughout the book, we see that there is no one correct way to process grief or move past it; everyone has to find their own way through.

One of the chief ways in which Fix the Universe differs from Break the Universe is that this time there is a “big bad” – the Gabi who wants to remove the membrane separating universes. But here again, Hernandez subverts the tropes: she’s not All-Knowing, she’s not Power Hungry or Pure Ego. She’s a girl who thinks she knows what the right thing to do it, and does everything in her power to achieve it. She’s clearly grieving, from almost her first appearance, for the world she’s losing, no matter how brave a spin she may be putting on it, and that grief affects her decisions as much as Sal’s did in Break the Universe. The presence of a “big bad” this time out shows that Hernandez didn’t want the second book to be a beat-by-beat repeat of the successful formula of the first, and Fix the Universe is all the better for that decision.

The book is about grief, and it’s about dealing with not being perfect, and it’s also about love. Love abounds on every page: parents’ love for their children, children’s’ love for their parents, spouses love for each other, friends’ love for each other. Every type of relationship is represented as equally valid: the Vidón’s monogamous heterosexual relationship; the Reál’s polyamorous conglomerate; Principal Torres’ marriage to her non-binary spouse whose pronouns are “they,” Senor Milagro’s widowership; the budding love affair between a pair of highly-specialized AIs; Sal being aromantic (which I’m not sure, on retrospect, was made explicit in the first book but which didn’t at all surprise me when revealed here). And the platonic love of friendship between the four main teens is given equal weight (with the implication that maybe, just maybe, there may be something more romantic between Yasmany and Aventura down the line) with the various romantic permutations we get to see. None of this surprises me, as Carlos Hernandez is one of the most joyously loving people I have ever had the pleasure of meeting.

I mentioned that this book is complete in and of itself as much as it builds off of the previous volume. All the major and minor plot threads are tied up, and if this is the last we see of Sal, Gabi, and their ever-growing co-mingled occasionally interdimensional families, I feel content. But there’s a hint near the end of this book of an intriguing untold adventure that I’d surely love to read. I hope that someday, Carlos Hernandez will bring us back to this world.